Introduction

Our decisions are built upon our understanding of the world.

For example, we decide whether to take a job based on our understanding of what we will do, where it will be, who we will work with, and what we will earn. Or a student may decide what class to take based on her understanding of what will be covered, the work required, and whether it is required for graduation. These all seem like personal considerations but they all entail our understanding of how other people understand the situation too: Does the employer understand the job description the same way as me; does the university recognize the class as meeting graduation requirements?

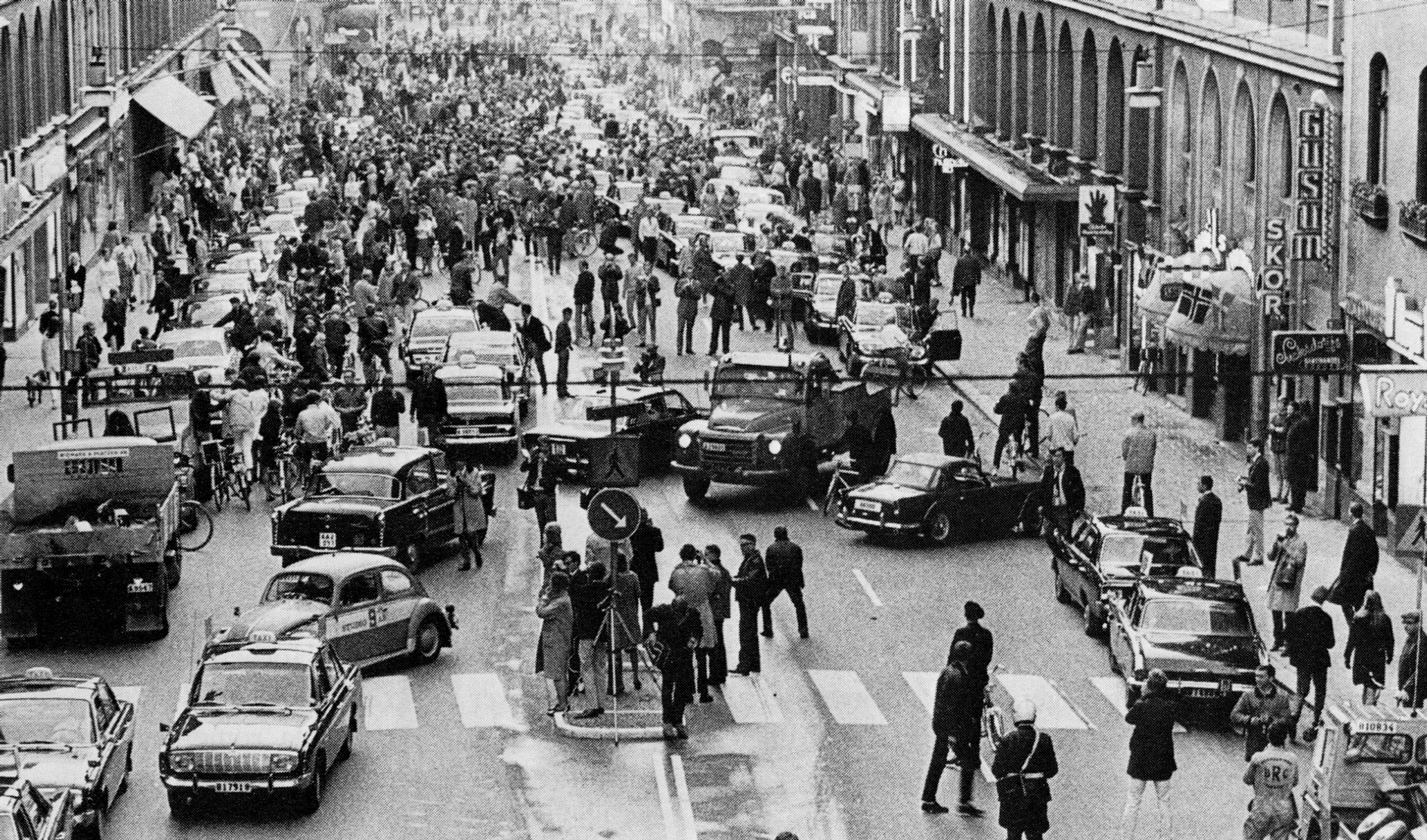

Some decisions are obviously based on group decisions. We each decide what side of the street to drive on based on what side we think everyone else will drive (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

In a society, even a decision like deciding what to eat for breakfast takes many inputs. Say you decide based on your understanding of what you have available, what is healthy, and what you think you will like. Likely you are deciding whether it is healthy is based on claims you have heard from other people or read, which you have to decide whether to trust.

If your decision-making draws upon your understanding of the world, it is equally true that for members of a group to all agree upon a common decision—to reach consensus—they should have some common understanding of the world. This includes a common understanding of relevant facts, of the mechanism by which group members agree upon a decision, and of the prior decisions made.

Blockchains utilize cryptography to provide a verifiable, tamper-resistant record of prior consensus. Cryptography can be viewed as a tool of verifiability and verifiability prevention—how to make certain claims verifiable and how to obfuscate certain information such that it is not verifiable. Digital signatures can be viewed as an example of the former, encryption as an example of the latter, and hashes as an example of both.

As blockchains help provide a common understanding of the world, blockchain consensus protocols use them as grounding to enable subsequent group decisions that update our view of the world. Each batch of decisions is a block that is added on to the blockchain. In the past decade, blockchains have emerged as a novel technological method of facilitating consensus at scale. Like all powerful early technologies, blockchain technologies have attracted their share of hype and demand critical scrutiny, but the potential of blockchain is immense.

The first—and still biggest—blockchain application was Bitcoin. Introduced by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008, people can spend the Bitcoin cryptocurrency in a peer-to-peer fashion without any intermediation by banks. The Bitcoin blockchain, also known as a distributed ledger, maintains the state of holdings. Everyone can verify the validity of this state for themselves.

What does money have to do with consensus? It comes down to the “double spend problem.” If Alice pays Bob some money, she should not then be able to turn around and pay that same money to Carol. With physical coins or cash (Fig. 3), this is obviously solved by the fact that a physical object can be in only one place at a time. (If someone tries to get around that physical law by making a copy of the coin or cash, we call that counterfeiting and punish it.) You can prove that you are entitled to spend a coin by simply handing it over. With a modern electronic payments, like with credit cards or wire transfers, we trust the institutional payment processor (for example, a credit card company or bank) to ensure that money is spent only once (Fig. 4). But what if we want a digital system where we do not need to rely upon any third parties like banks? If Alice pays Bob, we would all need to somehow agree, in a decentralized manner, that Alice has paid Bob and not Carol, and that therefore Bob can now spend that received money, not Alice or Carol. This is the job of a consensus protocol.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Bitcoin arose in a period of distrust of authorities, particularly financial authorities, in the Great Recession (Fig. 4). We will cover Bitcoin in detail in a later session. Suffice to say for now that, since Satoshi’s 2008 paper, the blockchain space has seen rapid methodological advances and interest has grown from a small pool of early adopters to the largest institutions and governments in the world. These players often have different incentives than the earlier proponents of cryptocurrencies, and their differing values are often reflected in technical decisions, as we will see.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Many grassroots advocates of cryptocurrencies referred to cryptocurrencies as “trustless.” First, note that the dictionary definition of “trustless” is “not deserving of trust” or “distrustful.” Neither of those is a particularly appealing quality for a money system, especially the first! Second, even in the sense that its proponents intend it—to denote that one does not need to trust anyone else—the description in our opinion misses the key point. Blockchains enable coordination at scales and in contexts where it was previously impossible without acceptance or imposition of central authority. When viewed in this light, while money has been the initial and primary use for blockchains, its implications are even broader. The financial system is first, but any area involving centralized authorities or platforms is potentially subject to disintermediation with blockchains.

A key component of coordination is verification. As President Ronald Reagan said, “Trust but verify.” Indeed, the first system described to use a cryptographically secured chain of blocks was to certify document timestamps (by Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta In 1991). In the case of money, we wish to verify that someone really has rights to what they claim and that given transfers really have occurred. In the case of a “smart contract,” another application of blockchains, we want to ensure that someone is really committed to a given contract and that its terms are followed. By allowing people to have mathematical confidence in certain facts (including prior consensus and the positions of other parties), blockchains enable freer peer to peer coordination without needing to rely on a third party arbiter. We will return to the concepts of decentralization and tamper-resistance later.

From a technical perspective, the field melds cryptography, algorithms, distributed systems, game theory, and more. Later sections will delve into all of these areas. We will start with a review of cryptography essentials. We will then cover Byzantine fault-tolerant consensus protocols, various algorithms to prevent Sybil attacks, Merkle trees and other primitives, “smart contracts,” privacy-preserving techniques, homomorphic encryption, network layer technologies, Lightning transfers and related methods, zero-knowledge proofs, and application case studies. We will also cover potential for misuse, examples of vulnerabilities, and governance.

Blockchains, and associated cryptographic technologies, are the most exciting subject in computer science today. It directly touches certain fundamentals of society in a way that few technologies do. To properly develop and apply it, we must understand it.